Call me Nick. Annoyingly I chose as my third novel in this series Melville’s Moby-Dick. I say annoyingly because it’s so massive I can’t possibly reread it all just for the purposes of this little post. I have read it though, and that is more than most people can say. And I’ve put it at number three, so there must be a good reason for that. Hence, let us begin part three of my ‘Top 10 Novels’.

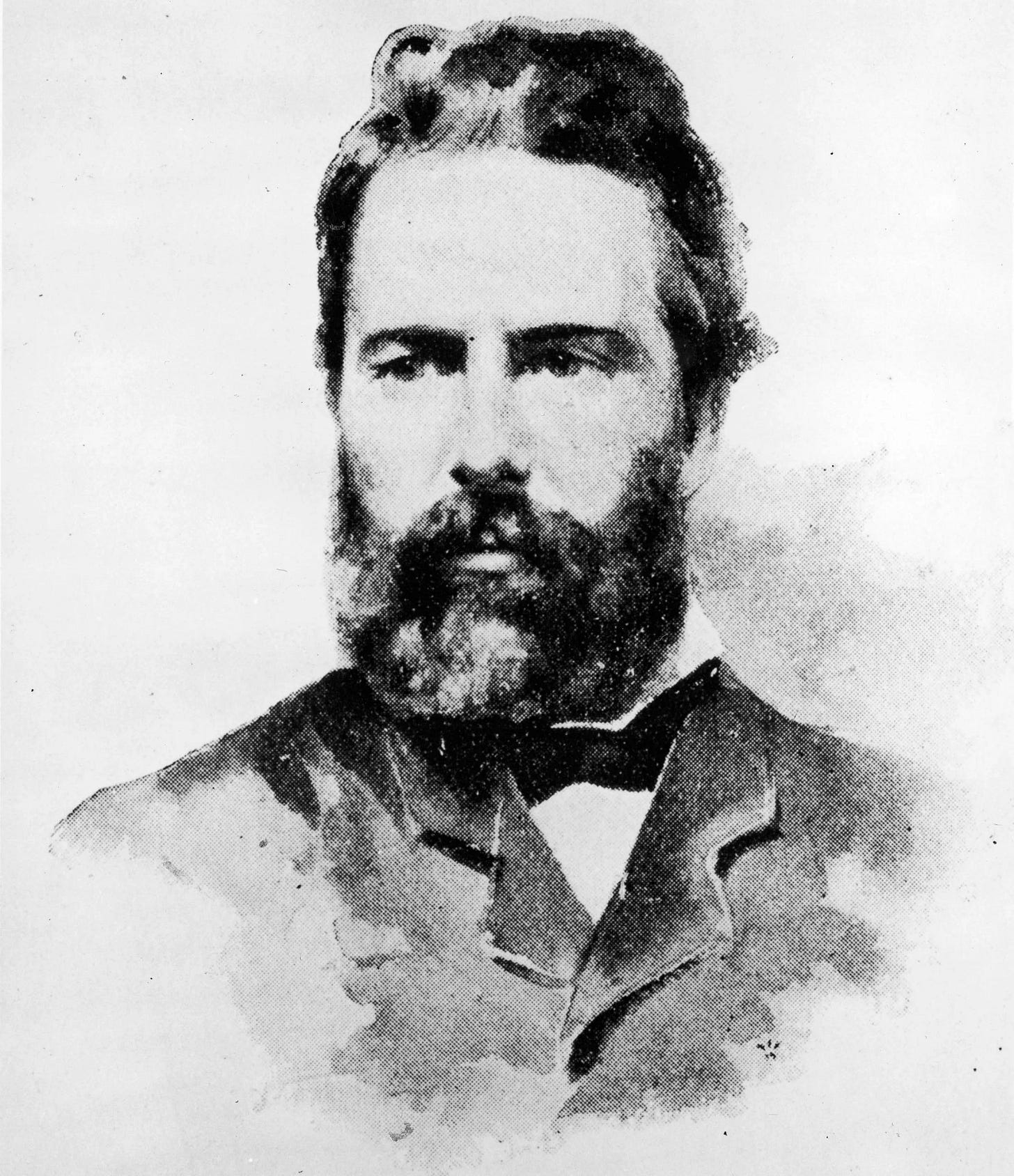

3. Herman Melville - Moby-Dick; or, The Whale

One of the few ‘modules’ I took at university that wasn’t Leftist garbage was ‘Classic American Literature’. What struck me immediately was the sheer wildness and epic scale of this body of the work. The almost obscene vitality and youth of this beast called ‘America’, and the brave attempts of those who would seek to capture it in poetry and prose.

Though I was encountering this writing in a scholarly setting—via brick-like anthologies comprised of thousands of wafer-thin pages—this was clearly an experimental literature, forged in what still felt like an experimental nation, the main works being written and published less than 100 years after its founding.

The key writers—Melville, Hawthorne, Whitman, Poe, Emerson, Thoreau et al—were tough people, with rough hands and rough beards. Or that was how they struck me at least. A couple were clean-shaven and Poe had a moustache, but you get the point.

Of these giants, Melville seems to me to stand tallest, especially as we are focusing on fiction, thus leaving aside the great essayists Emerson and Thoreau. And of Melville’s works, Moby-Dick is of course the masterpiece.

His other writing is significant and surprisingly varied. Bartleby, the Scrivener seems to prefigure Kafka. Billy Budd is a Christian allegory considered by many to be his second greatest work. But only Moby-Dick is widely attributed ‘classic’ status.

Like so many great works, it was not appreciated at the time of publication. Years after Moby-Dick was released (the novel, not the whale) Melville had to take a job as a customs inspector, a fact that seems truly absurd for the creator of a work of fiction so engrained in the popular psyche it has become archetypal.

And, again like most classics, that work is a far weirder and more idiosyncratic affair than one would imagine for a tale that has achieved incarnation as a children’s cartoon. Indeed, D. H. Lawrence called it "one of the strangest and most wonderful books in the world” (and he wrote some pretty strange stuff himself).

There is an argument that it is not even strictly a novel. Harold Bloom said “Moby-Dick is not a novel, it’s a prose epic. It’s a giant prose poem. A Shakespearean prose poem in fact. Quite deliberately.”

Although it is exciting at times, this is not slick storytelling. Melville ignores narrative convention whenever he feels it necessary. “Call me Ishmael”, goes the book’s beguilingly simple opening line, yet only at times are we seeing things from Ishmael’s perspective. Other times the narrative takes on an omniscience clearly not available to one man, as well as a depth of knowledge that would surely be beyond him.

Hence the novel, or whatever we call it, is part adventure story, part philosophy, part poetry, part diary, part almost scientific document, as Melville obsessively details the dimensions of the whale’s head and so on.

The scope of the work renders it almost pointless to quote from it extensively in a short piece, so I will just include a single passage from one of the book’s most memorable chapters, ‘The Whiteness of the Whale’, wherein Melville (who appears to be writing as himself more than Ishmael at this point) tries to pinpoint what it is about the colouring of the whale that inspires such terror:

Aside from those more obvious considerations touching Moby Dick, which could not but occasionally awaken in any man’s soul some alarm, there was another thought, or rather vague, nameless horror concerning him, which at times by its intensity completely overpowered all the rest; and yet so mystical and well nigh ineffable was it, that I almost despair of putting it in a comprehensible form. It was the whiteness of the whale that above all things appalled me. But how can I hope to explain myself here; and yet, in some dim, random way, explain myself I must, else all these chapters might be naught.

Though in many natural objects, whiteness refiningly enhances beauty, as if imparting some special virtue of its own, as in marbles, japonicas, and pearls; and though various nations have in some way recognised a certain royal preeminence in this hue; even the barbaric, grand old kings of Pegu placing the title “Lord of the White Elephants” above all their other magniloquent ascriptions of dominion; and the modern kings of Siam unfurling the same snow-white quadruped in the royal standard; and the Hanoverian flag bearing the one figure of a snow-white charger; and the great Austrian Empire, Caesarian, heir to overlording Rome, having for the imperial color the same imperial hue; and though this pre-eminence in it applies to the human race itself, giving the white man ideal mastership over every dusky tribe; and though, besides, all this, whiteness has been even made significant of gladness, for among the Romans a white stone marked a joyful day; and though in other mortal sympathies and symbolizings, this same hue is made the emblem of many touching, noble things—the innocence of brides, the benignity of age; though among the Red Men of America the giving of the white belt of wampum was the deepest pledge of honor; though in many climes, whiteness typifies the majesty of Justice in the ermine of the Judge, and contributes to the daily state of kings and queens drawn by milk-white steeds; though even in the higher mysteries of the most august religions it has been made the symbol of the divine spotlessness and power; by the Persian fire worshippers, the white forked flame being held the holiest on the altar; and in the Greek mythologies, Great Jove himself being made incarnate in a snow-white bull; and though to the noble Iroquois, the midwinter sacrifice of the sacred White Dog was by far the holiest festival of their theology, that spotless, faithful creature being held the purest envoy they could send to the Great Spirit with the annual tidings of their own fidelity; and though directly from the Latin word for white, all Christian priests derive the name of one part of their sacred vesture, the alb or tunic, worn beneath the cassock; and though among the holy pomps of the Romish faith, white is specially employed in the celebration of the Passion of our Lord; though in the Vision of St. John, white robes are given to the redeemed, and the four-and-twenty elders stand clothed in white before the great-white throne, and the Holy One that sitteth there white like wool; yet for all these accumulated associations, with whatever is sweet, and honorable, and sublime, there yet lurks an elusive something in the innermost idea of this hue, which strikes more of panic to the soul than that redness which affrights in blood.

This elusive quality it is, which causes the thought of whiteness, when divorced from more kindly associations, and coupled with any object terrible in itself, to heighten that terror to the furthest bounds. Witness the white bear of the poles, and the white shark of the tropics; what but their smooth, flaky whiteness makes them the transcendent horrors they are? That ghastly whiteness it is which imparts such an abhorrent mildness, even more loathsome than terrific, to the dumb gloating of their aspect. So that not the fierce-fanged tiger in his heraldic coat can so stagger courage as the white-shrouded bear or shark.

Such extraordinary passages, which demonstrate the immense breadth of Melville’s reading, as well as the elevation of this ostensible novel to the status of prose poem, show us why Melville is thought by many to be America’s Shakespeare.

The fact that he began his literary career confined more strictly to the seafaring adventure genre before creating Moby-Dick (which somehow only took him 18 months) is even more astonishing. In reminds me somewhat of Brian Wilson, that other American giant and greatest musical genius of the 20th century, who transmitted his celestial harmonies through the unlikely medium of songs about surfing, cars, and girls.

No one could produce a work like Moby-Dick in the present day. In our culture of uniformity, mediocrity, lack of education, lack of toughness, lack of attention, it would simply be impossible.

There are no men like Melville anymore. And no books—or artistic productions of any kind—like Moby-Dick. We can barely approach a work so monumental. All we can do is float around it and try to cling on, like Ishmael clinging to the life-buoy.

But if you are looking for a philosophical meditation on life versus death, God versus nature, freedom versus bondage, and man versus whale, I certainly recommend you give it a try.

Nice review, thanks.