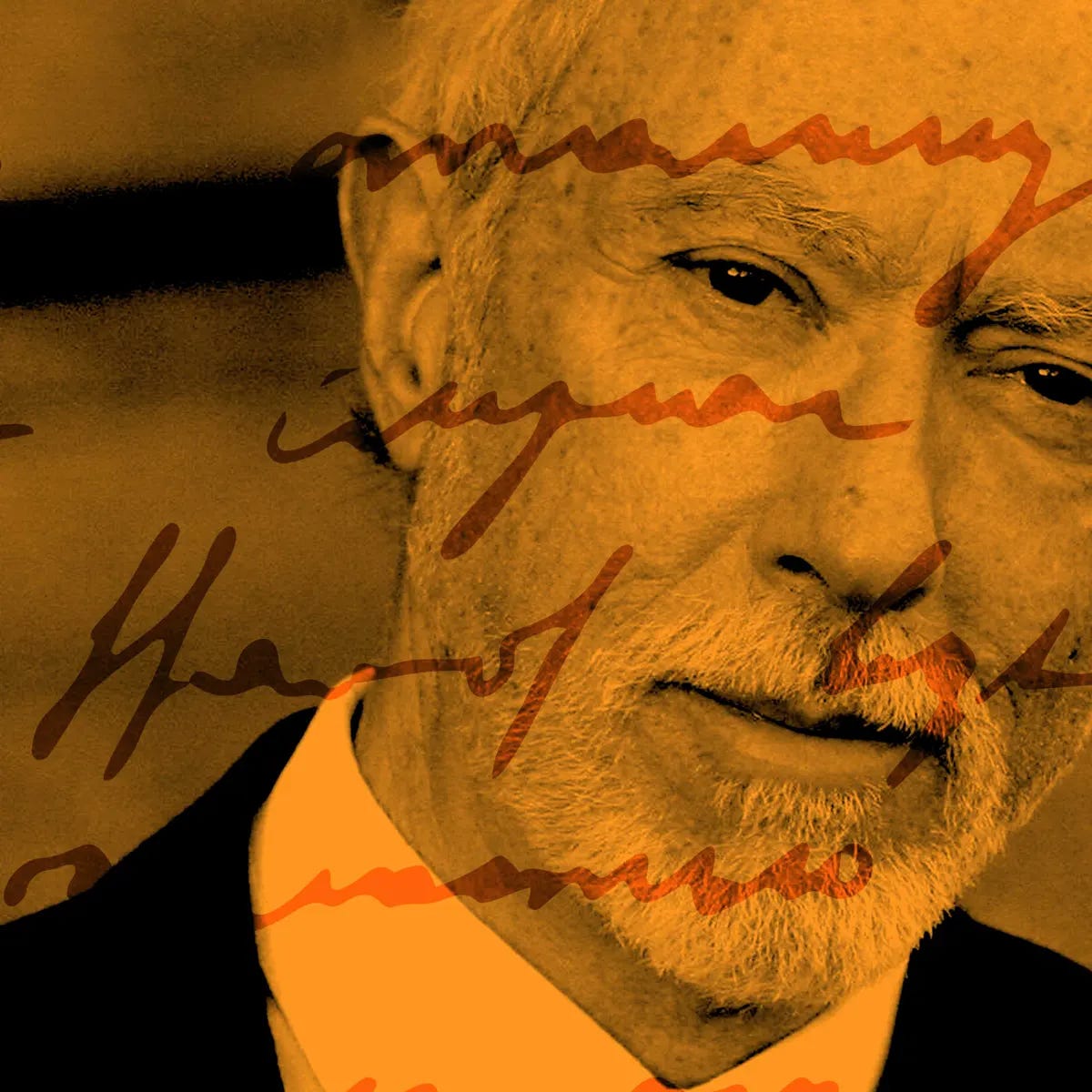

The fourth novel in my list is J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace. A relatively mainstream choice, it is one of the few genuinely great novels to have won the Booker Prize.

To me, it is Coetzee’s greatest work. The universities prefer things like Waiting for the Barbarians and Foe, because they fit most neatly into the category of ‘postcolonial literature’. There is nothing academics like more than to destroy art by cramming it into a political box.

Of course, Coetzee being a South African writing about South Africa, it doesn’t take that much cramming. The politics of South Africa is central to Disgrace, but there is far more going on beneath the surface, as the characters seem almost to insist on their own three-dimensionality, rejecting their potential status as political props.

There is also more going on on the surface, if you like, in Coetzee’s aesthetic achievements as a master stylist. We must always keep in mind that a novel is first and foremost a work of art, lest we fall into what Harold Bloom labelled the ‘school of resentment’—the Leftist academic obsession with viewing literature through the prism of various ‘isms’, a process that has effectively destroyed the study of literature in the West.

But let us now get into Coetzee’s great novel.

4. J. M. Coetzee - Disgrace

Published in 1999, Disgrace almost suffers from being too prescient; its far-sightedness in danger of being rendered banal by the daily horrors and absurdities of 2024. Attacks on white farmers in South Africa, for example, are now so commonplace and so horrific that the novel risks losing some of its symbolic resonance, especially given that the same subject matter is now fodder for conservative media documentaries. And rightly so, but Disgrace is not a documentary.

Coetzee, however, resists proselytising for any particular side, as he honours the harsh reality of his country, and the radically different perspectives of his characters.

Even more prescient than the violence of the novel’s second half is the sex scandal that comprises its first act. Coetzee appears to have predicted both the ‘metoo’ movement and cancel culture with unnerving accuracy in the university’s treatment of protagonist and ‘disgraced’ professor, David Lurie.

Following a reckless affair with a student, Lurie becomes a victim of the mob:

The gossip-mill, he thinks, turning day and night, grinding reputations. The community of the righteous, holding their sessions in corners, over the telephone, behind closed doors. Gleeful whispers. Schadenfreude. First the sentence, then the trial.

All that has really changed since the time this was written is the technology. No one would bother making a phone call when they can destroy you with a single tweet.

Radical feminism is also very much in effect, as we learn that:

On campus it is Rape Awareness Week. Women Against Rape, WAR, announces a twenty-four-hour vigil in solidarity with ‘recent victims’. A pamphlet is slipped under his door: WOMEN SPEAK OUT. Scrawled in pencil at the bottom is a message: YOUR DAYS ARE OVER, CASANOVA.

One can almost picture the YouTube video. Jordan Peterson screaming at entitled young women about Marxism and Carl Jung.

Early hints of what we now call ‘woke’ are also present. At his university hearing, Lurie is accused of offering “No mention of the pain he has caused, no mention of the long history of exploitation of which this is part.”

His automatic guilt by way of his very existence as an ageing white man may have still been somewhat particular to South Africa in 1999, but has now become universal Western doctrine.

Lurie offers various statements and confessions, but it is not enough: his interrogators want to know his intent, read his mind. Like the woke, like all true tyrants, they want him to genuinely embrace his re-education, not just go through the motions.

The phenomenon of ‘trial by media’ is also depicted with typical laser accuracy by Coetzee, as Lurie is confronted by a group of reporters who “circle around him like hunters who have cornered a strange beast and do not know how to finish it off”.

A teacher of the Romantic poets, Lurie offers a suitably romantic defence of his actions, and thus he must be cancelled. Though he is vain and pompous, all but the most ideologically warped reader will surely find themselves siding with Lurie in his contempt for his would-be judges and jurors.

That is certainly the case for this reader, and it has become more profoundly felt since the last time I read the book, having now been through a minor cancellation myself. Where previously I might have suspected the process would feel exactly as Coetzee describes, I now know that to be true. ‘Can confirm’, as they say.

However, these experiences in no way prepare me for the second part of the book, which ventures deep into the dark heart of South Africa’s tensions, taboos, and violent resentments.

Lurie leaves Cape Town (where, as it happens, I have also been since I last read the book) and goes to stay with his daughter, Lucy, in a town appropriately named Salem, no doubt an ironic reference to the witch trials held in the American historical city of the same name, with perhaps the further irony that the word actually means ‘peace’.

I will keep the spoilers to a minimum, suffice to say violence soon erupts, and the traumas of South Africa and the wider contemporary political scene play out in the reactions of the central characters.

David waffles about historical guilt, but is surprised by his own “elemental rage” against those who have wronged his daughter. Lucy ostensibly appears infuriatingly naive—the archetype we now know as the ‘libtard’, who would rather be destroyed than compromise his or her (or ‘their’) cosy beliefs—yet she turns out to be stoical and brutally pragmatic.

“Do you hope you can expiate the crimes of the past by suffering in the present?” David asks her. Lucy replies: “No. You keep misreading me. Guilt and salvation are abstractions. I don’t act in terms of abstractions. Until you make an effort to see that, I can’t help you.”

Much like her father, Lucy refuses to play the victim, even though it would be completely justified: “If there is one right I have”, she says, “it is the right not to be put on trial”.

Indeed, one theme of the novel is the attempt by individuals to free themselves from history and politics, and the ultimate futility of such a task, especially in a country like South Africa. The characters scrabble around trying to find a corner of the world they can exist in unmolested by circumstance. But the world tends to have other ideas.

There are rich layers of symbolism and symmetry throughout Disgrace that I cannot elucidate without spoiling the story, except to say that with Coetzee the reader can always rest assured they are in the hands of a master.

I should, though, say a word about Coetzee’s style. In Disgrace he perfects the third person, present tense technique previously employed in The Master of Petersburg, and used so effectively in subsequent works like Youth and Elizabeth Costello.

The novel begins:

For a man of his age, fifty-two, divorced, he has, to his mind, solved the problem of sex rather well.

In this ostensibly simple line we find economical storytelling, elegance, and rich layers of meaning that will only become apparent later, namely the hubris of the central character, for whom sex will soon prove catastrophic.

Elsewhere, trying to extract information from an inscrutable interlocutor is described as “like punching a bag filled with sand”. Another man is “wearing the same overlarge suit: his neck vanishes into the jacket, from which he peers out like a sharp-beaked bird caught in a sack”. One could cite many more, similarly perfect descriptions throughout the novel.

Nothing is wasted with Coetzee. Even the title’s single word proves impressively durable, providing the spine and recurring motif for the entire novel. The idea of ‘disgrace’ is applied variously to David, Lucy, and the unwanted dogs David helps to put down on his strange journey of penitence.

It is used perhaps most memorably when David finally confronts the father of the student with whom he had an affair:

In my own terms, I am being punished for what happened between myself and your daughter. I am sunk into a state of disgrace from which it will not be easy to lift myself. It is not a punishment I have refused. I do not murmur against it. On the contrary, I am living it out from day to day, trying to accept disgrace as my state of being.

Hopefully I have given you enough to want to read the book without giving everything away. Or reread it to find new gems. I have read it three times now, and each time has been more rewarding. Not a light piece in terms of theme, but made lighter by Coetzee’s exquisite craftsmanship.

A novel of rare perfection.